This Is Not Capitalism

this is your brain on central banking, regulatory capture, and financialization.

Allen Farrington & Sacha Meyers

n.b. this essay has since been adapted into a standalone chapter in the book, Bitcoin Is Venice (Amazon link here) by Allen Farrington and Sacha Meyers.

The everything bubble has popped. In the end it wasn’t PE ratios that imploded under their own stupendous highs, nor the conceptual insanity of negative rates triggering bank runs. The Euro didn’t fall apart (yet) and there was no hyperinflation (yet). It was an “exogenous shock” wot done it. We encourage readers to read this phrase with maximal eye-rolling sass, and to recall when we discuss the kind of macroeconomic macrobullshit that got us into this mess, which works perfectly well in every conceivable circumstance other than contact with the real world.

This puts us in a tragicomic position. In order to deal with this horrifically dangerous “exogeny”, we seemingly need to go into overdrive on the exact same measures that made us vulnerable in the first place: we need to print money like there is no tomorrow and throw it at everything that moves. That is literally the plan. That’s how we deal with emergencies now.

This essay is about the bizarre reaction we have noticed from a solid majority of the professional commentariat to the effect that this is the inevitable result of capitalism run wild. We are not sure what these people mean, or even think they mean, by “capitalism”. If they mean, “the regime of political economy dominant in the West since 1971 and particularly acute since 2009”, then they are correct on a technicality, but they are abusing the word. If “capitalism” means anything, that meaning ought to at least include the notion of preserving and growing capital. It can include other nasty bits and bobs, for sure, but it must at least include this.

The preservation and growth of capital is not happening, nor has it happened since before the dominance of the regime now misleadingly bearing this name. And so, it is somewhat concerning that people are lining up to both defend and attack “capitalism”, when the object of discussion could hardly be further from any worthwhile meaning of the word but is rather better described as: boosting aimless consumption, primarily with uncollateralised debt, by destroying the price signals for capital and depleting its stock. This may well be necessary for the sake of public health — we are not doctors, nor experts in biology, epidemiology, virology, or any similar field, and so we do not deny the merits of such an approach nor offer any views on their likely effectiveness. We just beg for the proper economic analysis of why we are in this position, and do our best to provide it.

This is your brain on central banking, regulatory capture, and financialization. This is not capitalism.

Money Is A Story

There is a vast literature on the question of ‘what is money?’ We present a simplified version for the purpose of establishing enough key points to keep the discussion moving along. Our account is by no means exhaustively wide nor exhaustively deep, but it is correct enough within the realms of what we cover. Readers looking for a more thorough treatment are encouraged to bookmark Shelling Out by Nick Szabo, Andreas Antonopoulos’s talk The Stories We Tell About Money, or for a longer, more academic read, The Theory of Money and Credit by Ludwig von Mises, and The Ethics of Money Production by Jörg Guido Hülsmann. But for the time being …

Money is a story. It is a story of what work has been done on credit that is yet to be redeemed. It is the Schelling point for universal credit. It is an IOU that everybody is willing to redeem (primarily because everybody is willing to redeem it) and hence that at every instance of its transfer is re-ordained with the ascription of economic value to work actually performed. Note that money is not a social construct, a collective delusion, or any other such denigration that snidely implies that nothing about money really matters and we could reinvent it all tomorrow if we wanted to. Money may be a story, but the qualities of the story matter a great deal. The truer the story, the better.

By ‘true’, we ought to mean that the process of transferring money has, and is trusted to have always had, the characteristics of censorship resistance and integrity assurance. We can think of this in cryptographic terms, as there is a ready analogy to be made to ensuring the security and validity of network communications. Transferring money is sending a message through the network of economic exchange. It is ‘censorship resistant’ if Alice knows her message is to Bob and only Bob; it is not diverted to Charlie, nor is it destroyed. It is ‘integrity assured’ if Bob knows the message is from Alice and only Alice; it is not really from Charlie, nor also to Dorothy, nor really from nobody at all.

When money is printed — whether this be bank notes or lines in a database — this is violating integrity assurance. It is equivalent to the printer extending themselves credit on the unwilling, and mostly unknowing, behalf of everybody. No work has been done that anybody is willing to redeem. No economic value has been created, or contracted to be created, to match the token now in circulation. Bob does not know his message of value transfer is from Alice and only Alice; it is not from anybody. The issuer has executed a man-in-the-middle attack on the structure of economic exchange.

And note this isn’t an old man yells at cloud rant against money creation in general in which we insist all economic activity must be conducted with gold. The money created by credit extension can be perfectly legitimate if the risk of the maturity transformation is priced freely by interest, borne by the equity holders of the lending institution, and mitigated with collateral they understand. But it is not if the risk is priced by political expediency, borne by nobody, and collateralised by everybody. It also doesn’t hurt to have the lenders know and consent to what is happening with their deposits, rather than suffering from the collective delusion that their funds are ‘in the bank’.

We will return below to the implications of taking the latter course of action. For now, bear in mind as we continue that money is universal credit and that its supply in a free market is a reflection of the reality of how much valuable work has been done. As Oliver Wendell Holmes put it,

“We must think things not words, or at least we must constantly translate our words into the facts for which they stand, if we are to keep the real and the true.”

There may be valid social or political reasons to compromise the censorship resistance or integrity assurance of money. Fighting a deadly virus might well be one of them. But there will be consequences; people will believe a story that simply isn’t true, but will act as if it is. We are currently living through the mother of all such consequences.

Stocks And Flows

Another decent definition of money is the most liquid form of capital. Although this is rather a circular definition, as ‘liquidity’ is traditionally conceived of as a measure of how quickly and easily an asset can be converted to ‘money’. It still tautologically works, as money can be converted to money in zero time and with zero difficulty, but it deserves to be padded out. We can say that money is the most salable asset: the asset that emerges with the property of being the most widely accepted in exchange for other assets, not to be consumed, but to retain value for later exchange. Note that, in a barter economy of only consumable goods, money adds little value beyond the administrative: it becomes easier to calculate exchange rates. Where money adds immense social value is in calibrating the exchange rates of goods that cannot be consumed, but rather are used to create consumable goods, or are used to create goods that are used to create consumable goods, and so on.

This all points to a higher analysis; money itself is not the most important aspect of capitalism. Nor is trade, nor markets, nor profits, nor even assets, but capital. ‘goods that are used to create consumable goods’ are a form of capital, but really, we mean something less tangible than any of the former; a kind of economic potential energy stored in the transformation of materials into higher and higher forms of complex good, but always ready to be rereleased to work again the same process of transformation. Seen this way, capital is not any particular thing or even behaviour — it can exist only as an emergent property of a social system in which the exchange of shares of ownership of private assets is seamless.

Capital is a stock. Its dimension is currency. It exists (and in theory could be measured) at any instantaneous point in time. Money and assets are also stocks, meaning they too can be measured at any point in time. But the numbers alone cannot have any independent meaning because they are dependent on the unit chosen to measure the dimension: Dollars. The number will be different in Euros, Yen, or Bitcoin.

Such measures as ‘revenue’, ‘profits’, and with a little leeway even ‘trade’ are flows. Their dimensions are currency over time. There is no such thing as instantaneous profit. Profit happens over time. This means that the numbers representing profit, and all flows, are sensitive to changing the unit measuring the currency, and the unit measuring the time. To avoid confusion on this account, we will assume Dollars per year as a default, but will at various points toy with this concept to make different points clear.

This might seem like semantics, but the distinction is key as follows: you need stocks to create flows, and you need flows to replenish stocks. Our entire analysis of how bankrupt (morally as well as factually) our financial system is can more or less be derived from the appreciation that this simple maxim is not widely understood. What does it mean more practically?

“The economy” is an aggregation of businesses, which are helpfully split into financial and nonfinancial (we hate the expression “the economy” and will endeavour not to use it unless avoiding it would be unbearably clumsy. It is a noun when it should really be a verb, because the way it is used refers to a flow, not a stock). Financial businesses oversee the allocation of liquid capital by matching the preferences of contributors of capital with regards to perceived risk, timeframe, and so on, with nonfinancial business projects with appropriate characteristics. Nonfinancial businesses turn liquid capital into illiquid capital — higher and higher forms of complex good — in an attempt to satisfy a perceived customer demand. If they make revenue, they are correct in a demand existing for such a good or service. If they make a profit, they have satisfied this demand efficiently; they have produced more than they have consumed. Profit is both payment to the providers of capital, and the opportunity to reinvest without requiring further external financing.

Nonfinancial businesses cannot create either revenues or profits without first being provided with capital. This might be as simple as saying that you can’t sell goods without first buying them or making them, and you can’t pay for the raw materials before you have made a profit unless you first have financing. Or it might be more complicated, but also more obviously linked to wealth creation, in that you need to buy a machine (a higher order capital good) that takes raw materials as an input and churns out something more complicated and more valuable. Clearly you don’t want the machine for its own sake; you want it for what it will produce. The machine has to be purchased with liquid capital, and then exists as illiquid capital. It can be liquidated if desired (i.e. sold for cash), but its primary value is as a form of economic potential energy. It is a stock that creates flows.

You need stocks to create flows, and you need flows to replenish stocks. You need financing to start a business, and you need profits to maintain one. Profits are required to pay back the financing, and will eventually give the business owner the ability to eschew financing entirely and maintain the business’s capital requirements sustainably and internally. This is as true for a single business as when aggregated to “the economy”.

The health of a single business, and the health of the aggregation of all businesses, should not be measured by ‘growth’ in revenue, or in profits, or even in capital, but in the ratio of profits to capital. The rate of return. And ideally, it should be (geometrically) averaged over a very long time — not only can no meaningful investment take place over a single year (accruals-based accounting exists in the first place to give at least some useful information over shorter time periods) but the length of credit cycles will obscure what is really happening over as long as ten or twenty years. A high rate of return is a high flow to stock ratio. If all the flow is reinvested, it will be the rate of increase of the stock, and reflect the meaningful growth of “the economy”.

Recall once more the ‘dimensionality’ argument: the ratio of profit one year to profit the year before is not even ‘growth’. It is an ‘increase’. Return on capital is a growth rate. Its units are one over time. Economic wellbeing and sustainability can only be sensibly measured with aggregated return on capital. Unsurprisingly, this is not at all how anybody does so …

‘GDP Growth’, And Other Useless Metrics

Widespread misunderstandings of money and capital, and of stocks and flows, come together to form a dangerous cocktail with GDP growth. In understanding how GDP is commonly discussed, and why that discussion betrays a stunning ignorance of money and capital, we will be in a position to evaluate the crisis we now face. This section marks the middle of the essay: the turning point between theory and practical analysis.

As we see it, there are (at least) three problems with ‘GDP growth’, all of which have some bearing on the crisis we now face, and which we will discuss in turn: i) the ‘economic wellbeing’ it claims to measure is in fact unmeasurable, ii) the ‘economic wellbeing’ it claims to measure is politically and socially irrelevant, and iii) it is not a ‘growth rate’ at all.

i) the ‘economic wellbeing’ it claims to measure is in fact unmeasurable: GDP is the total monetary value of goods and services produced in a region over a period. If somebody says “the economy” grew by 2%, they likely mean that the quantity of goods and services produced increased by that amount. Of course, not every quantity grew by exactly that amount. Some might even be shrinking. What matters is the total monetary value. When there is one fewer unit of A, costing $1, but one more unit of B, costing $2, GDP still increases by $1.

So far so good. This certainly seems ‘measurable’, so what’s the problem? Over time, human ingenuity comes up with new or improved goods and services. When that happens, there isn’t merely one more of A or B. There is something else entirely: C. GDP, which so far tracked how much the production of A and B increased, now also tracks C. Given enough time, demand for A, B, and C might disappear, so that GDP only consists of X, Y, and Z — none of which existed when records started. How can we then say that ‘the economy’ grew when it doesn’t make more of what it used to?

The unsatisfactory answer is that when C was invented, it had a market price which could be compared to those of A and B. In that way, the comparison stands. But this exchange rate between A and C only came into existence after C was invented. Beforehand, no amount of money could buy C. Innovation expanded our opportunity set so that capital could be allocated to the production of something new. The price of C only reflects the opportunity cost of its production and consumption after its discovery, not the value embedded in the discovery itself. There are no exchange rates to the future.

The value of discoveries compounds over time. A practical illustration of long-term ‘GDP growth’ makes its nonsensical nature plain. According to GDP, individual Vietnamese on average earn as much today as Americans did in the 1880s. Yet the Vietnamese have the same life expectancy as Americans did in the 1980s. Today’s Vietnamese live in a world of smartphones and penicillin, whereas 1880s Americans lived in an age of candlelight and often-fatal bacterial infections. The monetary value of their income might be considered comparable by economists, but that is because they do not, and cannot, measure the constant improvements brought upon by human ingenuity.

Economies do not ‘grow’, they ‘change’. And you can’t measure counterfactuals in Dollars.

ii) the ‘economic wellbeing’ it claims to measure is politically and socially irrelevant: we encourage readers to look into the blog post Democratic Domestic Product by Ole Peters, and the wider Ergodicity Economics research programme of which he is a part. But we will summarise the salient points here.

GDP growth is the growth in wealth of the average person, rather than the average growth in wealth of a person (the latter is Peters’ proposal for ‘DDP’). GDP growth is a plutocratic measure, that is indifferent to the higher moments of the distribution from which it is drawn. It is entirely possible for the wealth of every single person bar one to go down, while GDP growth goes up. In fact, something not too dissimilar to this seems to have happened in Europe and the US since the financial crisis. GDP keeps on climbing while median measures of income, disposable income, assets, net financial wealth, and more, have gone sideways or even down. The gains have increasingly been concentrated in higher and higher brackets of existing wealth, to the point where, at certain cut-offs, more than 100% of the gains have gone to some upper bracket. In other words, some groups are in fact getting poorer, but other groups are getting richer at a faster rate, such that GDP still grows.

While there is reason to believe that technological changes and geopolitics have contributed to this phenomenon, we will explain below why we think this can largely be explained by state enforcement of the dominant regime of political economy, and its abject ignorance of the principles of money, capital, and returns.

iii) it is not a ‘growth rate’ at all: as above, it is an ‘increase’. It is a difference between two flows. A growth rate is a return; a flow over a stock. Moreover, GDP isn’t even the correct flow one would need to compute a relevant return, because it is the aggregation of revenue, not of profit. By religiously focusing on this entirely irrelevant metric, it is almost trivially easy to end up doing both of the following:

· encouraging profitless revenue, which indicates a real demand, but an inefficient use of resources in satisfying that demand. Capital is one such resource — possibly the most important — hence:

· encouraging destruction or consumption of capital; or, a short-term high of consumption at the expense of the long-term ability to produce what we might like to consume. Think of a farmer eating seed rather than planting it. His consumption increases, but eventually he loses the ability to consume at all.

Equally useless without the proper context is stock market capitalisation. Obviously, it is more or less a good thing for stocks to go up, because it means that lenders of capital are getting a return, and companies that are proving the viability of their economic proposition can raise capital more cheaply. But there must be underlying economic success for this to be justified. Individual companies can always see their valuations grow out of line with their fundamentals, either on hype or entirely on merit as their prospects for the future are seen to be improving. But if valuations across the board are marching upwards vastly out of line with rates of return on capital, never mind with increases in cash flows or book value of equity, something is wrong.

There are two obvious contenders for what might be wrong, and which have the potential to reinforce one another in a deadly spiral: inflation and speculation.

By inflation, we mean to ignore such bullshit euphemisms as ‘quantitative easing’ and ‘market support’ and to direct the reader’s attention to the simple fact of artificial money being pumped into financial markets to increase prices beyond what reality is doing its best to get them to show. When prices go up because a currency is being debased, that is inflation. It might make a social and political difference if the price increases are in milk and bread, or housing and healthcare, rather than in financial assets, but economically it is irrelevant. It reflects only what the artificial money was first used to buy. Eventually it will dissipate to all goods and services. We will return below to the broader consequences of artificial money being directed specifically to financial assets, but for the time being, we simply mean to point out that the prices are fake. They do not reflect reality.

By ‘speculation’ we should be clear that we do not mean anything intrinsically negative. Speculation is usually rolled out by financially illiterate opportunistic rabble-rousers as a culprit for the consequences of intervention-induced market collapses, when in fact it is more than likely that speculation was trying to direct prices to reflect reality while artificial money was pushing in the other direction. We mean simply that financial market inflation can induce a certain kind of speculation that is unhealthy. If it becomes clear enough to market participants that the artificial money firehose will not be turned off, this actually reduces the incentive to speculate against the fake signals being provided by inflation and start contributing to inflation instead. In reviewing an early draft of this essay, Nic Carter kindly drew our attention to the large numbers of so-called ‘permabears’ who flipped long around 2016 when they realised this thing wasn’t going to stop.

Say you are a pension fund that needs an 8% return to meet its liabilities without difficulty. And say that stocks have been inflated to the point that you can in all honesty expect only a 2% return over the long run from here given reasonable assumptions about valuation metrics returning to something sensible at some point. You might be tempted to look for other asset classes that are not so corrupted. But if you are reasonably sure that artificial money will keep pushing prices up for longer than the time horizon over which you would otherwise expect a reversion, then it might actually be sensible to stay invested and get your 8% from inflation alone. This way, those who might otherwise be incentivised to contribute to correcting the effect of price manipulation are actually incentivised to contribute to reinforcing it, if the manipulation is strong enough in the first place.

When this vicious cycle gets into full gear, the idea of measuring ‘economic wellbeing’ solely by the increase (not growth) in stock market valuations, may be even more misguided than by that of GDP ‘growth’. It is not a returns metric. It says nothing about sustainability and in this specific scenario (the one we have been in for at least ten years) it is virtually guaranteed to be concealing highly unsustainable misdirection of capital, if not its outright destruction.

What Would Happen In An Economically Healthy Capitalist Society

Lots of things. We will go through some of them relatively quickly as they are more or less common sense and fall out naturally from the above discussion.

· You would be able to preserve wealth in money. Money is the stored and accepted value of work done in the past, redeemable for goods and services in the present or future. Money should not constantly decline in value. There are considerations regarding the conditions of credit extension and systemic leverage that make the issue more complicated and that we do not want to get into — but, all else equal, over a long enough period of time you would expect the purchasing power of money to increase roughly in line with aggregate return on capital, because the same past work done now has access to a greater amount of goods and services.

· This means you would only lend capital to risky enterprises because you want to, not because you have to in order to have any hope of preserving your wealth. This in turn means capital would be priced so as to accurately reflect society’s preferences for saving and consumption, and investment projects would be coordinated accordingly.

· Governments would either run surpluses or it would be acknowledged and accepted that they could institute emergency taxes. Printing money is a stealth tax on wealth that disincentivises holding money, as above. It has the same first-order effect on wealth transfers, but has hidden second-order effects of misdirecting capital due to political expediency and cowardice.

· Relatedly, governments would (or should) therefore be incentivised to act in the public interest at all times. They should not be beholden to stoking financial market inflation at all costs. They should not be ‘bought’ by Wall Street, nor have their banking laws written by bankers and their airline safety regulations written by unsafe airlines. If that means instituting economically disastrous short-term measures for the sake of public health (and to avert even more disastrous long-term economic results) there should be no wavering and no discussion. It should be done, and prices should be allowed to adjust to reflect the new reality without political consequence.

· Investment decisions could legitimately include greater social and environmental considerations without risking fiduciary liability. If you are constantly incentivised to increase short term profits, you will consider firing everybody and moving production to China. If you are incentivised to increase long term returns, you can double down on investment in your existing workforce and stomach the costs of more environmentally friendly inputs to production. The latter is clearly a broader social good, but is still easy enough to motivate and justify given the effects would otherwise be worst felt in the local communities where the workforce is based.

· Individuals and businesses would buy a lot more insurance. Preservation of wealth would be more important than the desperate need to grow it to stay ahead of inflation, and so the prudence of insurance against any and every “exogenous” disaster would be incentivised. Or, rather, it is obviously sensible in the first place, and so it wouldn’t be incentivised against.

· There would be no bailouts. Nothing would be “systemically important” because disasters — even “exogenous” ones — would be adequately insured against. When a business fails, its (willing) contributors of equity would be wiped out, its (willing) contributors of debt would not make whole, and its remaining liabilities would be covered by insurance. Government could even take a far more expansive role in protecting consumers in such cases given, i) it can afford it, and ii) there is no competing incentive to side with business, nor a moral hazard to side with both but encourage recklessness nonetheless.

· Company executives would be incentivised by long-term measures of growth in real value, not short-term measures of increases in per-share value. To be clear, buybacks are, in theory, a valuable tool to price capital properly. We do not argue against them in general, but we acknowledge that, in practice, they are often used as a means to enhance the latter rather than the former. We argue below this behaviour is entirely a pathology of the dominant regime of political economy of which this essay is a critique.

What Has Happened In Real Life

We have spent the past ten years working on the assumption that the supply and price of money is unimportant, that maximising the increase in GDP and stock market valuations is best for “the economy”, that it doesn’t matter that these numbers do not represent rates of return, and that ‘the average person’ is a meaningful concept whose economic wellbeing we can measure. This is your brain on central banking, regulatory capture and financialization. There is far too much to cover so we will stick to what you might have seen in the news lately.

Everybody Gets Levered Up The Wazoo: if you can’t save because money does not retain value, then you have to be fully invested. If capital has all been misallocated such that price signals are unreliable and losses are artificially sustained, then any minor advantage has to be levered to achieve a satisfactory return. And if interest rates are artificially low, this might even seem like it makes good business sense.

If all your competitors are levered to the hilt and you aren’t, even though you can optically afford it, you will be outcompeted. So you have to do it too. You can’t compete prudently in the long run if your competitors spend you to death on cheap capital in the short run. Even if there are no competitive pressures, there will be pressures from shareholders. As with speculation and buybacks above, there are perfectly sensible ways for businesses to use leverage to beneficially affect capital allocation, for themselves and for the market at large. But usually, this is because the company has visibility on likely variations in cashflows and slack to absorb shocks — not despite having no visibility and no slack.

There are forms of leverage other than debt. You can think of leverage more abstractly as an induced vulnerability to shocks — “exogenous” or otherwise — in exchange for a magnified gain in their absence. The more debt you have, the more vulnerable you are to shocks to cash flow, because you have no choice but to pay the interest. But in many ways, other vulnerabilities to shocks can be even more dangerous. At least debt is relatively transparent: you can infer from the financial statements how much of a shock you can afford. Other vulnerabilities are less inherently knowable. Supply chain decisions can be a form of leverage: to get the absolute lowest costs that can be sweated out your setup, you could choose a single supplier (say, in China) and instruct them to deliver right on time to drive your carried inventory to effectively zero.

Of course, this means that any shock to this setup whatsoever will break it entirely. There is no slack. It is exceedingly fragile. Which is more or less what we are seeing now, as Preston Byrne points out above. Not only are entire sectors grinding to a halt because they are operationally levered to the eyeballs towards one specific task and cannot adjust to even mildly different circumstances, never mind a quarantine, but this setup is precisely why we are in these circumstances in the first place. If we could have cut all contact with China in January there would be no crisis whatsoever. For some (cough cough US and UK) this would have been meant a reduction in imported tat. For others (cough cough Italy and Iran) this would rather more seriously have meant risking forfeiting strategic assets financed with Chinese debt under the Belt and Road Initiative. And so, obviously, tragically, the borders stayed wide open:

Swap out ‘freedom and democracy’ for ‘public health’ and you get the idea.

Declining to hold a cash balance is a form of leverage by omission. As is declining to purchase insurance it would really be prudent to hold. If the need to be levered gets desperate enough, many will even consider selling insurance as a way to top up returns, clearly indifferent to the long-term implications of this insanity, because the short-term pressures are too intense to care. The behavioural pull here should not be underestimated. If absolutely everybody is selling insurance, you might want to consider buying some, and yet this takes a special resolve.

Universa Investments exists more or less exclusively to run this trade. Do you think you could mimic them? Really? You are willing to lose a little bit more every day for ten years, waiting for the everything bubble to maybe, one day, pop? Or will you cave after 2 or 3? Will you get up and dance to the song that never ends? We haven’t seen any numbers but we imagine the past two months have been quite spectacular for Universa. Rumour has it 1,000% in February and 3,000% and counting in March. Not to detract from their genuinely brilliant analysis and essential work for their clients, but we can’t help but feel it is somewhat sad that, bet against absolutely everybody’s desperation, ignorance, and stupidity, is a viable strategy for a hedge fund. That said, it may be sad, but it is true, and we should not downplay or envy the valuable public service of those who pursue such a strategy successfully.

The Cantillon Effect Is Justified As A Public Good: The Cantillon Effect refers to the phenomenon that debased money is not distributed equally throughout society all at once, but is introduced in a specific place, giving its initial holders illegitimate purchasing power at everybody else’s expense. By the time the inflation washes through “the economy”, those who receive the artificial money last have had reduced purchasing power for as long as it takes them to at best catch up with everybody else. Also, as this is done sneakily, the new money isn’t priced in properly either, giving the Cantillon insiders an additional advantage. This is all rather amusing when you consider the likely hyperbolic response of financial elites and economists to the idea of ‘helicopter money’. For all its flaws, helicopter money is a substantially better and fairer idea than quantitative easing.

As per the dominant regime of political economy, the artificial money is introduced to the financial sector by means of ‘open market operations’ in which central banks add assets to their balance sheets in order either to boost the prices of financial assets, lower the borrowing costs of corporations, or both at once. This is justified because ‘growing GDP’ and ‘supporting the stock market’ are thought to be legitimate political goals — price signals, capital allocation, and rates of return be damned.

This means that everybody whose income derives from the face value of financial instruments benefits at everybody else’s expense. There is a decent argument to be made that, actually, the pensions of at least every past and present government employee are entirely dependent on these valuations, which justifies the social and political goal in the first place. But this obscures a crucial point: there is an extremely important difference between benefitting from increases in valuation because your wealth is tied up in those assets, and because your income derives from periodically skimming the value of those assets. Those in the latter position are actually in charge of all of this financialised, regulatorily-captured mess, and yet when challenged will wax lyrical about the savings of all those hard-working men and women in the former camp, pulling on your heartstrings until they snap.

Those in the latter camp tend to be exceedingly well-off already: bankers, market makers, hedge funds, mutual fund managers; the derivative professional services of each of the above: lawyers, accountants, corporate managers; corporate executives incentivised by options, hence in turn incentivised to buy back stock — not because the stock is undervalued and capital pricing in aggregate will benefit from this decision, but because valuation is not considered at all, and the intention is to temporarily boost the stock price in time for the options to mature and be cashed in. Each of the above makes out like bandits while little old retired schoolteacher grandmas are left holding the bag when markets inevitably collapse and their pensions evaporate.

And of course, when that happens, who can we expect to go on CNBC and beg Congress for bailouts but precisely the corporate executives, bankers, and the like, whose maintaining of this regime of political economy caused it all in the first place. In dire enough straits, some executive teams will have even have the stone cold cojones to buy back $3bn of stock with more or less the entirety of their company’s free cash flow, take combined options packages worth over $10m marked-to-market in one fiscal year, no doubt boosted higher in time for payday by all these buybacks, and then hold their employees’ jobs hostage in their negotiations for government bailouts:

These people’s wealth is determined almost exclusively by how high they can push flows — stocks and rates of return be damned. Everybody else is left with low or negative real returns and depleted stocks of capital and wealth. This is why GDP growth can be positive while almost everybody feels poorer. Almost everybody is poorer. Objectively so. Their savings have been stealthily taxed and handed to the already rich, while their everyday costs have gone up to reflect the dissipation of this inflation. Democratic Domestic Product growth (or lack thereof) would capture this, but nobody cares about DDP. GDP all the way, baby! Look at that S&P go!

Hey, wait, what happened? …

Financialization: in a world with only apples and oranges, bananas are new. But so are securities backed by mortgages on the properties of apple and orange farmers. Leading up to the last financial crisis, banks selling MBSs were contributing to GDP growth. They were incentivised to do so because their income came from skimming flows rather than growing stocks, and were allowed to flagrantly lie about the risks of doing so by captured regulators. Of course, the products themselves were largely highly toxic — not only did they not create any real wealth, they encouraged the staking of real wealth against synthetic versions of the same underlying toxic assets. Capital was depleted, but only in the very long run, long after the banks had taken their cut and passed on the hot potato (well, most banks).

But that cut was growth! GDP went up! Bank stocks went up! Bonuses went up! Everything went up until suddenly it went down to lower than where it started. This might seem hopelessly irrational, and in one sense it is. But that is not the sense in which anybody is incentivised to behave in a world in which returns must chase inflation, insurance must be sold rather than bought, and you know full well you will be bailed out if (or when) you blow up. And not this is not just banks: United Airlines is in an arguably conceptually identical position. It financialised its balance sheet (woo hoo growth!) for little reason other than to enrich its executives, blew up (but but but exogenous!), and now wants a bailout.

Nor is it all banks. It is perfectly possible to run a bank responsibly amidst such insanity. It just takes ethics and guts. Legendary BB&T CEO John Allison wrote an entire book about how flagrantly unethical banking and regulatory practices caused the previous crisis while he ran his bank well, including being subject to a Treasury shakedown to take TARP funds it didn’t need in order to help the likes of Citigroup and Merrill Lynch look less like dangerous lunatics. Readers might see the unfortunately suggestive title of this book and think Allison is solely proposing greater privatisation of gains. It is far more accurate to say he is proposing less socialisation of losses. Amen to that.

Ever eager to prevent the last crisis (or to be seen to have retroactively and heroically prevented the last crisis) much of the pre-GFC financialization has since been made illegal. And yet financialization continues apace. Imagine what grifting, off-balance sheet, 2010s shenanigans are on the cusp of seeing the light of day!

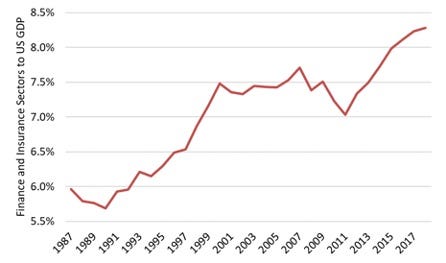

Consider the chart above of finance as a proportion of US GDP. Something is wrong here. Finance certainly ought to grow: if done properly it contributes enormously to societal wellbeing by allocating capital efficiently. This is all well and good. But it should not grow faster than everything else, because it typically charges a percentage fee of the face value of the assets or securities that pass through its allocating hands. For finance to consistently grow as a proportion of GDP, either it is simply upping its take — which might be reasonable within bounds, but raises questions of adequate competition in the sector and of possible regulatory capture — or it is making more and more MBS-like time bombs. It is spinning off flows of toxic financial exposure, of whose values it is taking a cut but not a stake, that don’t actually contribute to real economic returns, and hence to the aggregate growth in the stock of capital.

Once again, it isn’t just banks. In recent years this attitude seems to have firmly entrenched itself in just about every industry. Credit card income represents 40% of Macy’s profit. Patreon is now basically a payday lender. These aren’t extraordinary cases. They are exactly what you would expect when interest rates are artificially low for long enough: any business with enough customers and enough data on their customers’ purchasing behaviour can very likely borrow at low (fake) rates and effectively lend to customers at higher ones.

This arbitrage can even give them the leeway to make a loss on their actual good or service, furthering the widespread misallocation of capital away from things that can be sustainably profitable and towards facilitating indebted consumption of garbage:

The obsession with GDP growth that fuels financialization also leads us to forget that inventing new things to produce tomorrow is as important, if not more so, than increasing what is produced today. So-called capitalists in such a regime can resemble the Soviet Union apparatchiks (hardy flattering, we admit) who focused exclusively on increasing output at the expense of managing the inputs or improving the quality of anything produced. Since the value of genuine innovation can’t be measured, it tends to be discarded in a world focused exclusively on forever increasing such meaningless statistics as GDP and stock market capitalisations with no understanding of why these numbers ought to go up. In many ways it is like a cargo cult: when good things happen, stocks go up — so stocks going up must be a good thing! Official government policy from now on is for stocks to go up.

The effect of all this is that we make more of A, B, and C, and then move on to securitisations of A, B, and C, and synthetic securitisations of A, B, and C, and so on, until it all collapses. We never get to see X, Y, or Z. We never even think about what they might have been.

Conclusion

The dominant regime of political economy in the West since 1971, and particularly acute since 2009, has been built on a set of related economic fallacies: that there are no adverse consequences to manipulating the price and supply of money; that economic wellbeing can be measured by increases in flows of revenue rather than the growth rate of profit over capital; that such measures as GDP growth and stock market capitalisation ought to be maximised at all costs; and that the growth rate of the average matters, but not the average growth rate.

Had we built a capitalistic society on the principles of sound money and long-term returns, a great many institutions and incentives would likely be radically different to what we see today. The structure of economic production would be far more robust to shocks, far more inclusive in its creation and distribution of wealth, and far less corrupting in its rewarding of political cronyism.

That we have not has led to dire consequences that the coronavirus outbreak has exposed and exacerbated, but which existed nonetheless and, given enough time, would have found another way to explode. The factors we falsely deem to cause economic wellbeing are in fact fine-tuned to accelerate our inevitable descent into ever greater fragility, inequality, extraction, and financialization, and, ultimately, to the total depletion of capital.

This is your brain on central banking, regulatory capture, and financialization. This is not capitalism.

Thanks to Nic Carter for edits and contributions

In addition to those cited, thanks to Ben Hunt, Parker Lewis, and Mark Spitznagel, who did not directly contribute, but to whom we owe an intellectual debt

You can follow Allen on Twitter @allenf32

Allen has not yet convinced Sacha to create a Twitter account, so you can only follow him on Medium for now. He is thinking of getting a TikTok.